Brands Are Living Beings

Your car smiles at you. Your phone finishes your sentences. Your watch cheers when you move. We’re surrounded by tech brands pretending to be people and we love them for it. The more human our machines become, the more humanly we behave with them.

This behaviour isn’t a coincidence. It’s a psychological design, an old marketing trick with a new, AI-sized engine behind it.

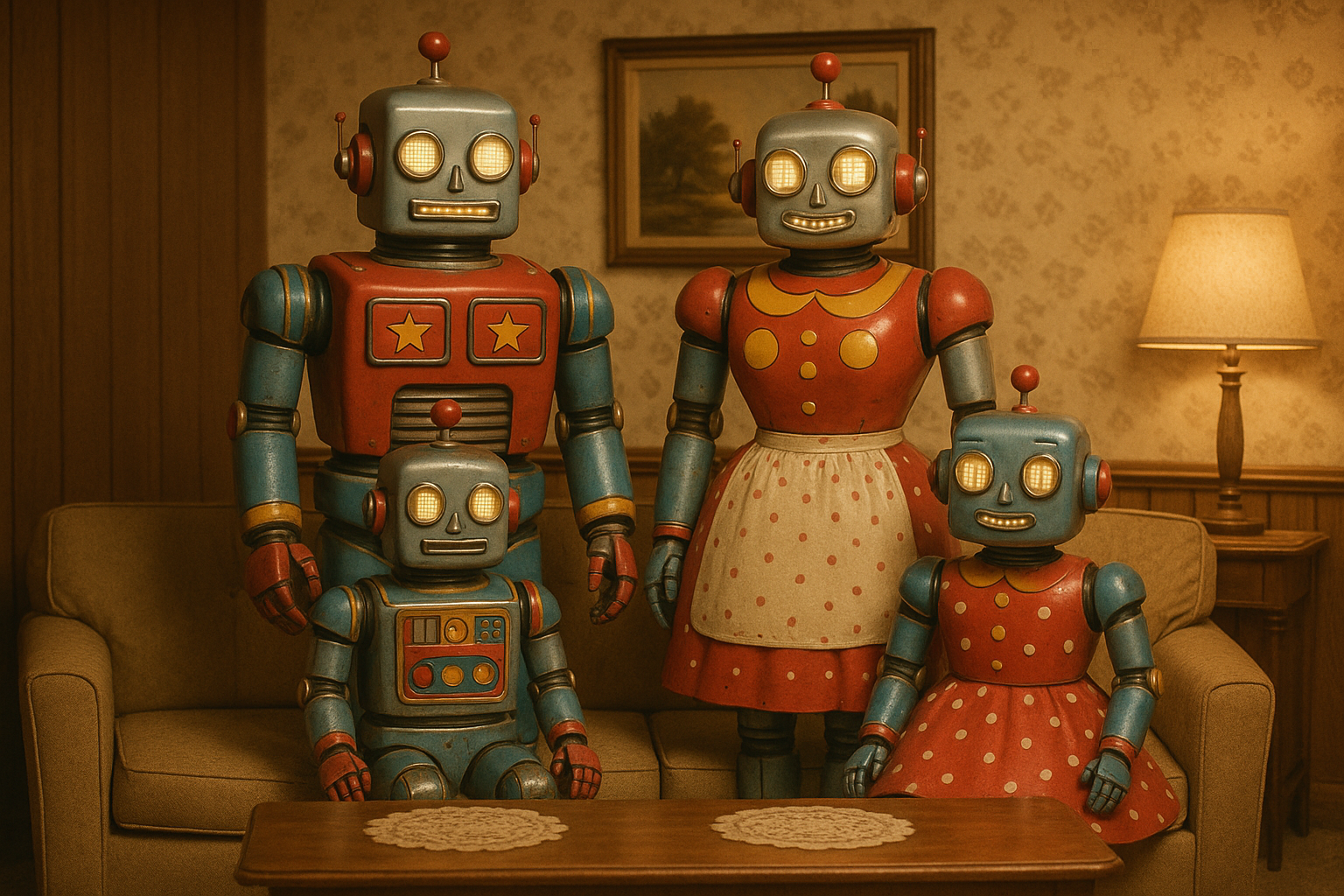

Brands are living beings. The difference between brands people use and brands people love lies in a single phenomenon: brand anthropomorphism, the art of making companies feel human. Brand anthropomorphism transforms products into personalities. When we say, “My Fitbit nags me,” or “Alexa understands me,” we’re not being cute, we’re confessing attachment.

Marketing scholars started documenting this back in 1998, when Susan Fournier’s landmark study Consumers and Their Brands revealed that meaningful relationships require brands to develop distinct personalities. Every piece of modern marketing vocabulary (brand voice, brand image, brand identity) springs from this insight. Nearly a decade later, Pankaj Aggarwal and Ann McGill’s paper Is That Car Smiling at Me?mapped the mechanics: consumers of successfully humanized brands exhibit stronger positive emotions and, crucially, greater anticipated separation distress.

This anthropomorphism isn’t accidental. It’s engineered, through visual cues, verbal patterns, gender assignments, and first-person communication. It’s deliberate. It’s strategic. And it’s the secret weapon behind artificial intelligence’s conquest of the mainstream.

AI didn’t triumph on technical merit alone, it succeeded through superior storytelling, often by accident. In 1943, two researchers called a simple on/off function a “neuron,” giving math a heartbeat. In 1956, John McCarthy named the field Artificial Intelligence – a phrase far bolder than the science it described, but irresistible to imagination and funding alike.

Fast-forward to 2022: OpenAI’s first GPT model remained largely unnoticed for ten months. The breakthrough came not from algorithmic leaps but from packaging the technology in a conversational, human-like interface. The core technology stayed the same; the persona changed everything.

Now, AI as a category enjoys anthropomorphic advantages by default, the very name suggests human-like intelligence. And as the market matures, we’re about to witness a new kind of tech brand war: not over features or speed, but over personality compatibility. These battles will hinge less on technical merit and more on consumer–brand relationships.

It’s a cycle capitalism has played before. In the mid-20th century, as Jack Trout observed, superior products stopped being enough. Companies moved from touting unique selling points to crafting reputations, and eventually, to owning cognitive real estate. When features and images became indistinguishable, success shifted from what you made to how you lived in the consumer’s mind.

AI markets are racing through that same evolution. As capabilities converge and commoditize, positioning becomes the real differentiator, and positioning, ultimately, depends on mastering the psychology of relationships.

Human psychology maps relationships along two primary dimensions: warmth and competence. We trust personalities that balance both traits. Consumer–brand relationships follow the same pattern.

AI’s anthropomorphic positioning delivers competence in abundance, perhaps too much. The category radiates futuristic capability but often lacks emotional warmth. True brand love requires both.

The companies that crack this code – humanizing technology while preserving credibility, will capture disproportionate market share. The most successful AI companies won’t just build better algorithms; they’ll craft better stories about who they are, what they value, and why they matter. In the end, the AI revolution may not be won by the smartest machines, but by the most human brands.