Sensible Market Segmentation: Pick a Beach

Every tech startup tells itself the same lie: “Our product is for everyone.” Then they wonder why nobody’s buying. The truth sits in plain sight and most founders never see it. There’s a predictable pattern to how tech innovations spread or fail to spread through society.

The Roger Revolution

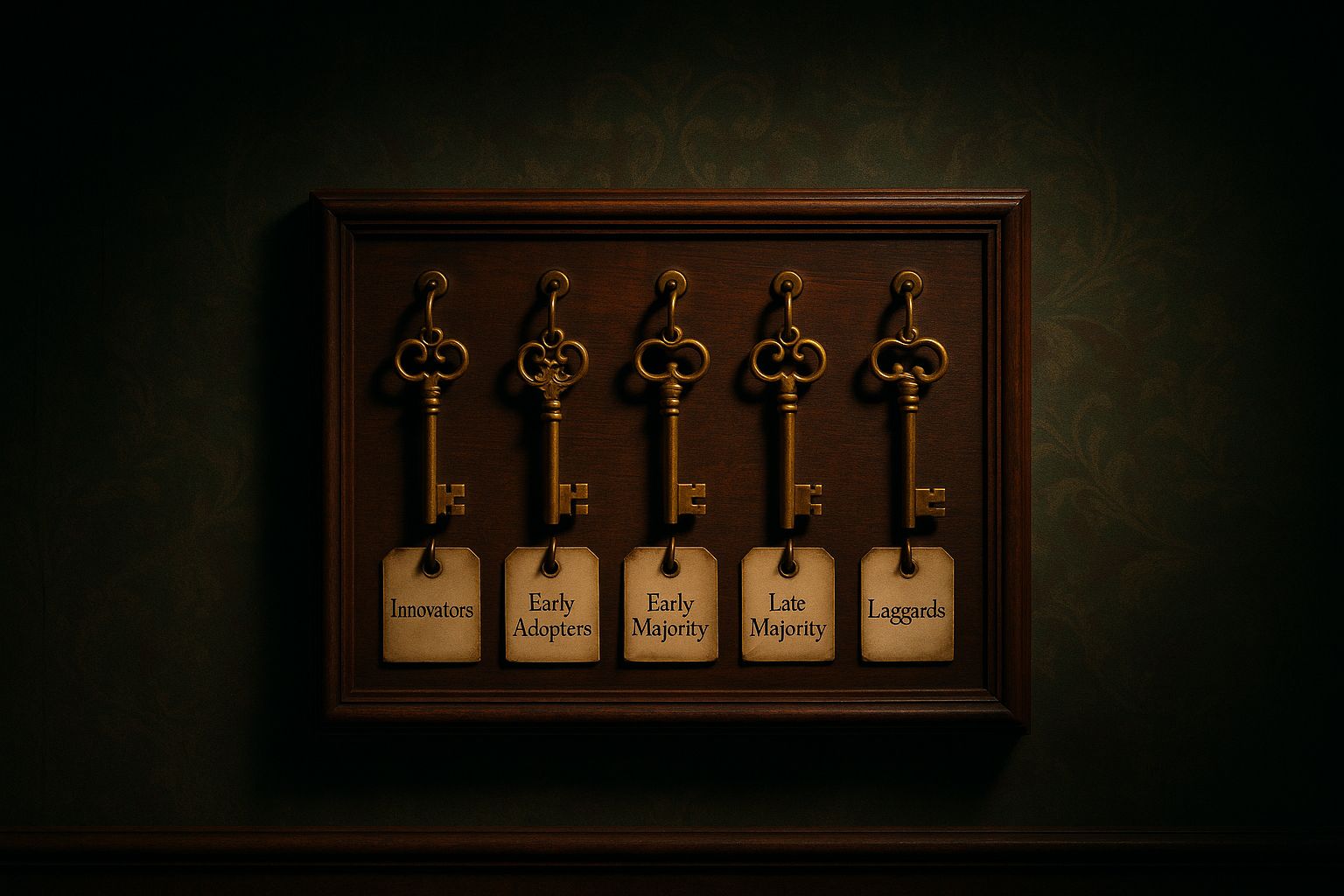

In 1962, while Madison Avenue was still treating consumers as an undifferentiated mass, sociologist Everett Rogers dropped a framework that would eventually become gospel in Silicon Valley. His innovation diffusion curve mapped how new ideas move through populations, and it wasn’t a straight line, it was a believable bell curve with distinct segments ergo distinct psychometrics. These segments were innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards.

Innovators (2.5%) have high risk tolerance and don’t need social proof. They’re motivated by the technology itself – they want to try it first, understand how it works, figure out what’s possible. They’ll buy your product when it’s barely functional because the idea excites them. Price is rarely the barrier; availability is.

Early Adopters (13.5%) are looking for strategic advantage. They’re not just curious about technology – they’re thinking about how it positions them ahead of competitors or peers. They’re willing to take calculated risks because they see the potential payoff clearly. They bought Uber when it was just black cars in San Francisco, Instagram when it was just photos with filters. They become your evangelists not because they’re nice, but because being first gives them status.

Early Majority (34%) waits for proof. They’re not risk-averse; they’re evidence-driven. They need to see the technology working reliably for people like them before they’ll invest time and money. They joined Dropbox after their colleague stopped losing files. They adopted standing desks after someone they knew actually fixed their back pain.

Late Majority (34%) adopts when the cost of not adopting exceeds the cost of change. They’re skeptical of innovation claims and generally satisfied with what they have – until circumstances force their hand. They joined Zoom in March 2020 because remote work became mandatory during covid. For them, necessity drives adoption, not opportunity.

Laggards (16%) are oriented toward the past. They have deeply embedded ways of doing things and view change with suspicion. They adopt only when the old solution literally stops functioning (or existing). They’re not irrational; they’ve optimized their lives around existing solutions and see no compelling reason to relearn. They view change with deep suspicion and will cling to the old way until it’s physically impossible.

More simply, through iPod adoption: Innovators camped outside Apple stores on launch day, eager to be first with this untested music player. Early Adopters made those iconic white earbuds a status symbol, deliberately wearing them as a fashion statement that said “I get it.” The Early Majority waited until their friends raved about having “1,000 songs in your pocket” and finally ditched their CD players around 2004-2005. The Late Majority only bought iPods when their car’s CD player died and every new car came with an iPod dock, making the switch unavoidable. Laggards kept using their Discmans until discs or those devices couldn’t be found in stores anymore.

Rogers showed us something profound: this isn’t random. It’s not about demographics or income brackets or zip codes. It’s about psychology – risk tolerance, social influence, and relationship with change itself. This is market segmentation at its most fundamental level, based not on superficial characteristics but on how humans actually adopt new behaviors.

And here’s why it matters: this pattern has held across virtually every significant tech innovation of the past six decades. Personal computers. Mobile phones. Social media. Cloud computing. Electric vehicles. The curve doesn’t lie.

The Chasm

But Rogers’ elegant bell curve hid a trap. In 1991, Geoffrey Moore looked at the corpse-strewn landscape of failed tech companies and spotted the pattern. They’d all made it past the innovators and early adopters. Then they died.

Moore’s insight: there’s a chasm between early adopters and the early majority. Not a gap. A chasm. And most innovations fall into it.

Why? Because early adopters and the early majority want fundamentally incompatible things.

Early adopters are visionaries. They’ll tolerate broken products, missing features, and nonexistent support because they’re buying into a future. They want revolutionary change and they’re willing to piece together solutions from duct tape and API calls.

The early majority are pragmatists. They want proven, reliable, complete solutions that integrate seamlessly into existing workflows. They need references. They need support. They need it to just work on Tuesday morning when they have a deadline.

Most startups optimize for visionaries and assume pragmatists are just “the next group.” They’re not. They’re a different species.

Trying to cross the chasm with the same pitch that worked on early adopters is like speaking English louder to someone who speaks Mandarin. Volume doesn’t solve the translation problem.

D-day Strategy

Moore’s solution is brutally counterintuitive: get smaller before you get bigger.

Think about the D-Day invasion. The Allies didn’t spread forces evenly across Europe’s coastline hoping something would stick. They concentrated overwhelming force on specific beaches in Normandy, secured those positions, then expanded from strength.

Pick one beachhead market and dominate it utterly. Not “CRM for everyone.” Not even “CRM for small businesses.” Try “CRM for real estate agents in competitive urban markets.” Specific enough to feel claustrophobic.

Why does this work?

Pragmatists act on references from people like themselves, from the segment they belong to. A real estate agent doesn’t care that your software works for insurance brokers. They want to know it works for other real estate agents. When you own one niche completely, references proliferate within that segment. Adoption becomes self-reinforcing.

You can deliver the “whole product.” Early adopters tolerate incomplete solutions. Pragmatists demand everything works out of the box, documentation tailored to their industry, integrations with tools they already use, support staff who speak their language. You can only deliver this level of completeness for one segment at a time.

You can afford focused distribution. Where do real estate agents congregate? What publications do they read? Which conferences do they attend? Which associations do they join? Narrow focus makes these questions answerable and the answers affordable.

Salesforce didn’t try to sell “enterprise software” to “businesses.” They sold sales automation to sales teams at small and medium businesses. Dominated that beachhead. Then expanded.

Slack didn’t sell “workplace communication” to “companies.” They sold it to tech startups, then tech companies, then expanded outward. The pattern repeats because the psychology repeats. Each segment of Rogers’ curve has distinct motivations, risk profiles, and decision-making criteria. The early majority won’t behave like early adopters no matter how much you wish they would.

Know Your Segments, Win Your Market

Here’s the uncomfortable truth tech entrepreneurs need: product isn’t strategy. Understanding the psychometrics of each adoption segment and planning acquisiton accordingly should be the core of strategy.

Innovators are motivated by novelty itself. They’ll forgive almost anything if you’re genuinely doing something new. Early adopters are motivated by competitive advantage. They want the edge that comes from being early to a transformative technology. The early majority is motivated by productivity and risk mitigation. They want proven solutions to known problems. The late majority is motivated by necessity and social pressure. They adopt when not adopting becomes the riskier option. Laggards are motivated by… well, they’re mostly just waiting for you to pry their preferred solution from their cold, dead hands.

Each segment requires different messaging, different features, different support, different pricing, even different distribution channels. Treating them as one market is popular startup stupidity.

Success depends on how fast you can get one segment to recommend your product within that segment. Not across segments. Within.

When you achieve critical mass in one niche, when adoption becomes self-sustaining through word-of-mouth within that specific community – you’ve crossed the chasm.

Then you can pick the next beach to invade.

This is why Rogers’ diffusion curve combined with Moore’s chasm framework isn’t just theory, it’s the most empirically validated model of market segmentation in tech. It’s predicted the trajectory of smartphones, social networks, enterprise SaaS, consumer IoT, electric vehicles, and countless other innovations.

The market doesn’t care about your pitch deck. It cares about whether you’re disciplined enough to concentrate force on one beachhead at a time. Most founders fail because they try to boil the ocean. They pitch to everyone, optimize for no one, and drown in the chasm wondering why the early majority never showed up.

The ones who win? They know exactly which beach they’re taking, exactly why pragmatists in that niche have a compelling reason to buy, and exactly how to turn those early pragmatic converts into the reference-generating engine that pulls in the rest of the segment.

Subscribe

You may also like

Coal, Carbon, and Computers

Climate Cost of the Digital Age

Why Before What

Sinek's Golden Circle proves purpose beats features every time

How To Talk To AI

The business leader's guide to AI orchestration